Can a Writer Retire?

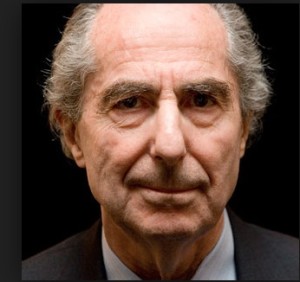

Thursday, February 27th, 2014Philip Roth, long one of my favorite writers, recently announced his retirement. In his apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side there’s reportedly a post-it note stuck on his computer screen that says, “The struggle with writing is over.”

But how does a writer retire? Particularly one as single-mindedly devoted to his craft as Roth.

For more than fifty years Roth wrote constantly, turning out book after book from the novella Goodbye Columbus in his early twenties in 1959 to his last, Nemesis published in 2010. More than thirty books, some better than others, but all with legitimate literary merit.

For more than fifty years Roth wrote constantly, turning out book after book from the novella Goodbye Columbus in his early twenties in 1959 to his last, Nemesis published in 2010. More than thirty books, some better than others, but all with legitimate literary merit.

According to a piece by David Remnick in the New Yorker, “Roth’s writing days were spent in long silence-no distractions, no invitations entertained, no calls, no e-mails. After I wrote a Profile of Roth, around the time of the publication of “The Human Stain,” we would meet every so often, and he told me the story of how a friend had asked him to take care of his kitten. “For a day or two, I played with the cat, but, in the end, it demanded too much attention,” he said. “It consumed me, you see. So I had to ask my friend to take it back.” Four years ago, he told me that he was interested in trying to break the “fanatical habit” of writing, if only as an experiment in alternative living. “So I went to the Met and saw a big show they had. It was wonderful. Astonishing paintings. I went back the next day. I saw it again. Great. But what was I supposed to do next, go a third time? So I started writing again.”

My question is what will he do this time? Go back to the Met over and over and over?

Nevertheless Roth claims he has already said what he had to say. In Remnick’s piece, Roth quotes the boxer Joe Louis “‘I did the best I could with what I had.’ It’s exactly what I would say of my work: I did the best I could with what I had… I don’t think a new book will change what I’ve already done, and if I write a new book it will probably be a failure. Who needs to read one more mediocre book?”

I repeat my question, what will he do this time. Keep returning to the Met? He’s not young. He turns eighty this year. But his mind is still sharp. His skills have barely diminished, if at all. And writing a book is not an effort that demands physical strength like mining for coal or loading heavy furniture onto a moving van to help a still-active crime writer move from his island home to Portland. Most writers, with some obvious exceptions, are not people who worked simply to make money, to amass a fortune and, having amassed it, now want to spend the rest of their days doing something more fun like chasing potential trophy wives. Or doing something more noble like helping hungry children in Africa or starting a foundation.

Philip Roth is and I believe always will be a writer. Being a writer requires a certain turn of mind. To sit (or in Roth’s case stand) at a desk and dream what it is like to live someone else’s life. Whether you’re Roth who, no doubt, will be long remembered for his best works or James Hayman who almost certainly won’t, a writer writes. And both Roth and I are writers.

Somebody once asked Mel Brooks who is 87, when, if ever, he planned to retire. He reportedly responded “Retire? Retire from what? I sit in a chair with a pencil and pad and when I think of something that makes me laugh, I write it down.”

I’m considerably younger than either Roth or Brooks. I’ve still got most of my hair, though now it’s mostly silver instead of its original black. And I’m certainly not as obsessive or disciplined about my writing as Roth. I do go to parties. I do go to movies and museums. I do have lunch with friends. But at the end of the day, or more accurately, at the beginning of the next day, I go back to my writing. I feel pretty much the way Brooks does. There’s never any reason to retire from a writing career other than Alzheimers , the horrible disease that felled British writer Iris Murdoch.

Harper Lee wrote one book. She published To Kill a Mockingbird in 1961. And, as far as anyone knows, has written little, if anything since. Like Mel Brooks she’s now 87. I don’t know how she did it or how she spends her days. But I think she’s an anomaly.

Some retirees play golf. Others do good works. Or take care of their grandchildren. Or travel. I’m not a golfer and at this point have no grandchildren. I have enough money not to be forced to put on a blue jacket and welcome people to Walmart. While I’ve served on a few boards, I’m not very good at it. I’d like to be able to travel but nobody ever said you can’t travel and still write. In fact, writers have the unique luxury of legitimately being able to deduct the cost of travel from their taxes as research or reading tours. Even Amtrak is reportedly offering writers free train rides as “fellowships,” to write and I for one love writing on trains.

Having recently completed and survived a move from our island home to a house in Portland, I’ve started, after an enforced hiatus, to get back to writing my fourth McCabe/Savage thriller. I’m 17,000 words in and I like what I’ve got so far and, more importantly, I’m enjoying the days I get to spend inside my characters’ heads. It’s where I want to be.

I hope, like Elmore Leonard or Mel Brooks, I’ll still be at it when (and if) I hit 87. I just hope that if I am, someone will want to read about the people I bring to life inside my head and on my computer.